Texas megadonor Alex Fairly joined forces with the GOP’s ultraconservative wing. He didn’t like what he saw.

"Texas megadonor Alex Fairly joined forces with the GOP’s ultraconservative wing. He didn’t like what he saw." was first published by The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan media organization that informs Texans — and engages with them — about public policy, politics, government and statewide issues.

Sign up for The Brief, The Texas Tribune’s daily newsletter that keeps readers up to speed on the most essential Texas news.

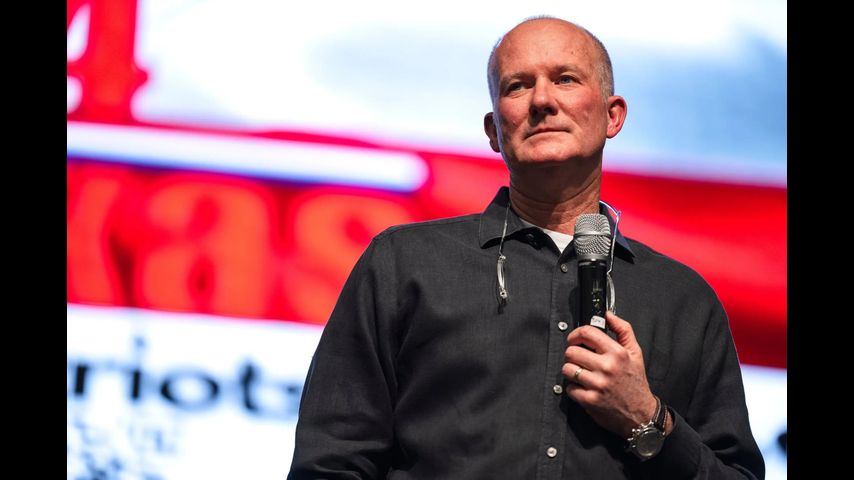

AMARILLO — In mid-September, Alex Fairly accepted an invitation to spend the day with one of the state’s richest and most powerful political megadonors.

He jumped in his private plane and flew down to meet Tim Dunn, a West Texas oil billionaire, at his political headquarters located outside of Fort Worth.

For five hours, Dunn and his advisers walked Fairly through the network of consulting, fundraising and campaign operations they have long used to boost Texas’ most conservative candidates, target those who they deem too centrist and incrementally push the Legislature toward their hardline views.

The two men talked about political philosophy and strategy. They discussed the Bible at length. Fairly was impressed, he said, if not surprised by the sheer magnitude of Dunn’s “political machine.”

“I think most people underestimate how substantial and how many pieces there are that fit together and how coordinated they are,” Fairly said in an interview with The Texas Tribune.

Dunn ended the tour with an ask: Would Fairly be willing to partner with him?

It was a stunning sign of how suddenly Fairly had emerged as a new power broker in Texas politics. Three years ago, few outside Amarillo had heard the name Alex Fairly. Now, the Panhandle businessman was being offered the chance to team up with one of the most feared and influential conservative figures at the Capitol.

Over the past year, Fairly had also poured millions into attempts to unseat GOP lawmakers deemed not conservative enough and install new hardliners. He sought to influence the race for House speaker and rolled out a $20 million political action committee that pledged to “expand a true Republican majority” in the House.

He had chosen a side in the raging civil war between establishment Republicans and far-right conservatives — and it was the same side as Dunn. Seemingly out of nowhere, he had become the state’s 10th largest single contributor for all 2024 legislative races, even when stacked against giving from PACs, according to an analysis by the Tribune.

But after mulling it over, Fairly turned down Dunn’s offer. It wasn’t the right time, he said.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/8e1105059e2c45bea4f3a2dd5dda600a/02%20-%200410%20Alex%20Fairly%20EH%20TT%2053.jpg)

And a few months later, Fairly began to question whether it would ever be the right time. Ahead of the 2025 legislative session — where his daughter Caroline would be serving her first term — Fairly dove deeper into the dramatic House leadership election, aiding efforts to push out old guard Republican leadership whom he believed were making deals with Democrats at the expense of conservative progress.

But the more he dug, the more he didn’t like what he saw: dishonest political ads, bigoted character assassinations and pressure campaigns threatening lawmakers over their votes. Fairly eventually realized much of what he thought he knew about Texas Republican politics was wrong.

He said he’d been misled by people in Dunn’s orbit to believe House Speaker Dustin Burrows was a secret liberal. Those misconceptions informed his efforts to try to block the Lubbock Republican from winning the gavel.

“I thought it was all true,” he said. “I didn’t know Burrows one bit. I just was kind of following along that he was the next bad guy. And it wasn’t until, frankly, other things happened after that that I started just asking my own questions, getting my own answers.”

As Fairly’s perspective shifted, he said he felt a moral obligation to correct course — and to try to get others, like Dunn, to change their behavior, too.

His political awakening could have seismic implications for Texas politics. Just last year, he seemed positioned as a second Dunn-like figure who could add pressure and funding to the effort to push the Legislature further right. Even now, he still supports many of those same candidates and concepts in principle. But he has come to condemn many of the methods used to achieve those goals by Dunn and his allies. Dunn did not respond to a request for an interview or written questions.

“When we spend time attacking each other and undermining each other in public and berating people's character — particularly if it has a slant that isn't completely honest and truthful — I think we are just eating each other,” Fairly said. “At some point you began to do more harm than you're doing good.”

An apolitical start

Fairly grew up in a middle-class family in Alamogordo, New Mexico, one of four siblings raised by public school teachers.

Today, Fairly, 61, said he’s just shy of being a billionaire — though he hates talking about his money and insists his children were not raised in a wealthy home. He built his fortune slowly over the course of a few decades through a career in insurance and risk management. He and his wife, Cheryl, have lived in the same two-story brick house for more than two decades.

As a child, Fairly and his family attended Church of Christ services three times a week. They were Christian legalists, he said, who viewed salvation as something achieved through a strict interpretation of Biblical rules. Still a devout Christian, Fairly said he no longer identifies with legalist teachings.

After high school, Fairly drove 311 miles east to the Panhandle where he attended West Texas A&M University in Canyon. He enrolled as a music major, playing the trombone, but later switched to computer science. There, he met Cheryl, a violin major who currently plays in the Amarillo symphony. After graduation, the two settled in Amarillo where they had five children.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/1e86ca800cf70493e47e19b1279ff3e2/03%20-%200409%20Alex%20Fairly%20EH%20TT%2006.jpg)

After more than two decades climbing the insurance industry ladder, Fairly in 2016 started the Fairly Group, a risk management consulting firm with a client list that now includes the MLB, the NFL and Major League Soccer. From there, he’s spun off multiple successful health care companies.

With money came new opportunities for philanthropy and civic engagement. Two years ago, Fairly pledged $20 million to his alma mater to build an institute to promote traditional “Panhandle values,” centering faith, hard work and family.

“He does feel a burden for stewardship for the resources that he's blessed with,” said Walter Wendler, the president of West Texas A&M University who worked with Fairly on the institute.

But for most of his life, he wasn’t concerned with politics. Fairly didn’t register to vote in Texas until he was 37 years old. He didn’t vote in the 2016 presidential election, though he says he voted for President Donald Trump in 2020 and 2024.

He admits even now, he isn’t well versed on legislative process or the latest political news. He doesn’t consume much Texas media — his morning routine consists of waking up at 5:30 a.m. to read the Bible and the Wall Street Journal.

In recent years, Fairly started to throw his support behind politicians who aligned with his values.

One of the first big checks Fairly ever wrote to a candidate was in 2020 to support Republican Ronny Jackson’s first bid for Congress. Fairly and some other wealthy Amarilloans swooped in after the former White House doctor made it into a primary runoff against an establishment Republican backed by Amarillo’s business community.

Fairly funneled more than $300,000 into a PAC to support Jackson, who positioned himself as the more conservative firebrand candidate.

Jackson, now serving his third term in Congress, said he was grateful to Fairly for his support.

“Alex is not beholden to anyone. He's his own man,” Jackson told the Tribune. “Whenever he thinks it's appropriate to break ranks and support somebody else … he's not afraid to do it. He’s not fearful of what the repercussions might be.”

That attitude would drive Fairly’s decisions as he waded deeper into Texas politics.

Finding conservative allies

In 2022, Fairly sued the city of Amarillo to block plans to build a civic center. Taxpayers had voted the project down a few years earlier and he thought the city council’s decision to move forward circumvented voters’ desires. The city countersued, drawing Attorney General Ken Paxton’s office into the case as a neutral party. But at the trial, to Fairly’s surprise, Paxton’s office took his side. Fairly said he’d never spoken to Paxton before the lawsuit, but eventually donated $100,000 because he wanted to support an elected official for “having the courage to stand up for normal people.”

Fairly would stick with Paxton the following year when the state House impeached him on 20 charges of corruption and imperiled his scandal-prone career. Fairly gave Paxton $100,000 on the first day of his impeachment trial, and then another $100,000 a couple months after he was acquitted.

By then, Fairly was aligning with other hardline Republicans. In 2022, he gave $250,000 to Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick, the Senate’s conservative standard bearer, because of his faith.

In spring 2023, Fairly started giving to Dunn’s Defend Texas Liberty PAC — one of the top donors to both Paxton and Patrick, and an aggressive contributor in Republican primary campaigns to oust sitting members targeted for not being conservative enough. A political consultant had advised Fairly to use Defend Texas Liberty to run ads in local Amarillo city council races, he said. He also gave to the PAC to support Paxton’s impeachment defense.

“I didn't know who they were. I hadn’t heard of them. I was, frankly, way more naive then. I wouldn't have even thought to check,” he said.

This was Fairly’s entry into Dunn’s constellation of political operations that have played a major role in moving Texas further to the right in the decade and a half since the Tea Party movement burst onto the scene. Those organizations include his PAC, which donates to far-right candidates; an affiliated conservative media outlet, Texas Scorecard; and other policy groups he’s funded over the years that promote anti-tax, anti-immigrant, and anti-LGBTQ+ positions, often using incendiary rhetoric. Last year, for instance, a group connected to Dunn mailed voters' primary attack ads insinuating that a group of Republican House members who had voted to commemorate Muslim holidays had approved of Sharia law in Texas.

These groups advocate for Christianity in public spaces, and have pushed for policies including allowing prayer in public schools. Dunn is a central player in the Christian nationalist movement, which believes the United States was founded as a Christian nation and its laws should reflect certain Christian values. Fairly, for his part, says he is devout Christian but breaks with Dunn over his views on religion and government.

By September 2023, Fairly had given Defend Texas Liberty $222,000 in donations.

Then, in October, a reporter and a photographer for the Tribune witnessed the infamous white supremacist Nick Fuentes walking into the PAC’s headquarters for a visit that lasted more than six hours. The meeting drew attention to several other racists and antisemitic figures connected to the PAC and other Dunn operations. For example, the PAC’s treasurer posted on social media that Jews and Muslims worship a “false god.”

Dunn, in a rare public statement issued through the lieutenant governor, called the Fuentes meeting “a serious blunder.” Afterward, Dunn shuttered Defend Texas Liberty and launched a new PAC called Texans United for a Conservative Majority.

Fairly said he thought the Fuentes meeting, which occurred after he donated to Defend Texas Liberty, was “utterly unacceptable” and it was a learning lesson for him to pay closer attention to where he sends his money.

A detente with Phelan

In early July, then-House Speaker Dade Phelan received an unexpected text message. Fairly wanted to meet.

Phelan, R-Beaumont, had just won his primary runoff race. It had been an ugly, expensive election and Fairly was one of the top backers of his challenger David Covey.

Over the past year, Phelan had become the face of the establishment conservatives in the Texas House whom critics had labeled as RINOs, or Republicans in name only — even after he oversaw two of the most conservative Legislative sessions in recent memory. He was blamed for the House’s inability last session to pass a private school voucher program — one of Gov. Greg Abbott’s top priorities and Fairly’s, too. Phelan also refused to bend to conservatives who wanted to end a tradition of appointing both Democrats and Republicans to chair House committees.

But Phelan’s greatest sin, according to his detractors, was that he presided over the House in 2023 when it impeached Paxton, who they saw as a conservative hero being politically persecuted.

In early 2024, Fairly decided to put his muscle behind ousting Phelan from office, writing a check for $200,000 to Covey.

Fairly also became a major contributor to other House Republican primary candidates running on being pro-school voucher, pro-Paxton, anti-Democrat and oftentimes anti-Phelan.

In total, Fairly spent at least $2.24 million in 2024 on 20 GOP legislative candidates.

When Covey pushed Phelan into a runoff, Fairly dumped an additional half a million dollars into the race, pouring a total of $700,000 into a district nearly 650 miles away from Amarillo.

Phelan held on to his seat by 389 votes. The night of the May runoff election, he criticized the dishonest campaigns against him “from Pennsylvania guys and West Texas against me,” referencing attacks funded by billionaires Jeff Yass, a national voucher advocate, and Dunn.

In early August, Fairly flew his plane down to meet Phelan in his Beaumont office.

This was not a peace offering. If Phelan was going to be the next speaker, Fairly wanted to convince him to run the House differently.

The mood was tense. Fairly suggested that Phelan’s management of the House contributed to the divisive atmosphere and that “Republicans would get along so much better if there was someone with more of a tight-fisted way of leading the chamber,” Phelan recalled in an interview.

Phelan told Fairly he’d been naive. He explained the House was just different; it’s the Wild West and it’s impossible to manage 150 members with an iron fist.

In the course of the conversation, Phelan pointed to a picture of his children on his desk and shared with Fairly what they had experienced watching their father endure a deceptive war on his reputation, including mailers that called Phelan a communist, commercials that said he took money from an LGBTQ+ group that “celebrated trans visibility day on Easter Sunday” and mailers that falsely claimed Phelan, a Christian, wished to celebrate Ramadan instead of Christmas.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/626e067d959139f87ca0cb479b7e9f57/05%20-%200126%20House%20District%2021%20MF%20TT%2003.jpg)

“You paid for all of that,” Phelan said he told Fairly.

Many of the ads were paid for by groups that Fairly didn’t fund, but he was remorseful nonetheless.

“I didn’t care if I had [paid for] 5% of it or 50% of it,” Fairly said. “I said, ‘if I had a role in that, I apologize.’”

They left the meeting cordially, but not as friends.

Looking back, Fairly said a seed was planted that day.

“That was the first person that said [to me], ‘Hey, dude, this is just not as simple as you think,’” Fairly said.

Fairly launches a PAC

With election season behind them, lawmakers were steeling themselves for the next big battle: the race for House speaker — leader of the lower chamber who plays a key role in what bills are passed.

Fairly, too, was ready to make his mark. Even after his visit with Phelan, Fairly had no intention of supporting him.

Throughout the summer and early fall, Fairly would continue to watch House veterans and incoming freshmen sling mud over the speaker’s race. He concluded that he wanted a speaker who was elected by a majority of Republican House members. And he didn’t want the speaker to make deals with Democrats that would weaken their ability to achieve conservative goals.

In December, Rep. David Cook, R-Mansfield, emerged as the candidate of the anti-Phelan flank. And with Phelan’s supporters facing intense political pressure, the speaker dropped out of the race.

Fairly was feeling hopeful that the party would rally around Cook. But soon after, Burrows, one of Phelan’s closest lieutenants, declared he was running. The next day, the House GOP Caucus held a meeting to select the party’s choice for the gavel. Burrows and Phelan loyalists walked out in protest of the process. Cook won the caucus vote. Burrows called a press conference and claimed he had the votes to win, with an even split between Republicans and Democrats backing him.

“I saw this thing devolving into chaos again, and I was focused on Republicans being together,” Fairly said.

The campaigning continued without a clear winner. Typically an inside baseball process, the speaker’s race was framed to voters as a conservative litmus test for House members. State officials including Paxton and outside groups launched intense pressure campaigns to convince Burrows’s supporters to switch their vote to Cook. Lawmakers’ personal cell phones were aired publicly in ads accusing those supporting Burrows of party disloyalty.

As the bruising fight reached an apex, Fairly launched a PAC called the Texas Republican Leadership Fund with a staggering initial donation of $20 million.

In the announcement, Fairly said Republicans need to reject the small group of Republicans who teamed up with Democrats to cut a “joint governing agreement” and come together to elect a speaker. Just like Dunn, Fairly would use his money to threaten Republicans to get in line.

“I thought that we would probably need to do some primary-ing of people,” he said of his plans for the PAC. “It wasn't so much a PAC as it was an amount of money that … members would need to pay attention to.”

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/8b37deca1ae88e39834467ce85822940/06%20-%200421%20Alex%20Fairly%20EH%20TT%2070.jpg)

“I cannot be that”

In December, with the House speaker race still undecided, Cook asked Fairly for a favor: Meet with incoming freshman John McQueeney of Fort Worth and convince him to switch his vote for speaker away from Burrows.

At this point, Fairly was invested in Cook’s success. He was talking to Cook often and had sent him $50,000.

McQueeney was surprised to get a call from Fairly — who had bankrolled his primary opponent to the tune of $100,000.

“Why me?” McQueeney remembered thinking.

Hostility in the speaker race was bubbling over. Members like McQueeney were under fire, as mailers and text messages were flooding their districts, leading to a nonstop barrage of angry calls from voters.

Six days before Christmas, the two men met in a private airport terminal conference room in Fort Worth.

Fairly said that he imagined McQueeney was under a ton of pressure, and yet “you don’t seem to be wavering,” McQueeney recalled. Fairly wanted to know why.

McQueeney respected Burrows and Cook, but felt Burrows had a more conservative voting record and more experience as a leader in the House.

He told Fairly he did not believe Burrows had made any deals with Democrats, but Fairly wasn’t buying it.

Then, McQueeney showed Fairly the dozens of text messages, calls and voicemails he received each time an attack blast that included his cell phone number was deployed in his district.

While they were meeting, another text message had just gone out. It accused the incoming freshman of cutting a deal to elect “liberal” speaker Dustin Burrows. The angry calls were starting to roll in.

Sitting across from McQueeney, Fairly said he didn’t feel the attacks on McQueeney were honest. Yet he knew where they were coming from.

“Most of that operation that was run to come after McQueeney was put together by Tim [Dunn]'s organizations. It was choreographed by them,” Fairly said.

As Fairly flew himself back to Amarillo, he thought about the PAC he launched days earlier and the “in your face, hammering” tone of his announcement that he would primary people who he disagreed with.

“I went home thinking, I cannot be that. I'm not going to use my money to do that,” he said. “It became this moral and ethical thing for me. … I can't do with the PAC what I was planning to do.”

Caroline’s crossroads

As Fairly was having second thoughts about his role in the speaker race, so was his daughter — who was days from being sworn in for her first term as a state lawmaker.

Rep. Caroline Fairly, a 26-year-old freshman, had publicly aligned with Cook, but she said she never felt like she had a real choice: Picking Burrows would have branded her a RINO.

Burrows did not respond to an interview request.

“I'm going along, I'm a conservative. You know, I ran to ban [Democratic committee] chairs, and this is the option I have,” Caroline recalled in April, sitting in her new Capitol office. “I had been fed, frankly, that the people on the other side are just not good people.”

She liked Cook and respected his conservative bonafides. But she was bewildered by the accusations that Burrows was a liberal sell out. Burrows, after all, had a conservative record. He was the author of last session’s “Death Star bill," that sapped local government power, particularly in blue cities where progressive policies were being passed.

“That's where I started thinking, wait, hold on. This doesn't seem right to me. I met with Dustin Burrows. He's a logical conservative, an impressive guy,” Caroline said.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/013b82dee7e031625cdf4cdacbe04d84/07%20-%200225%20House%20LW%20TT%2006.jpg)

She took notice that Cook was also publicly courting Democrats, promising them in an open letter “an equal voice in shaping policy.” She felt it was hypocritical to criticize Burrows while Cook was doing the same thing. Cook, reached for comment, said he was "not interested in rehashing the past."

But Caroline, the youngest member of the Legislature was under tremendous pressure and scrutiny. She came into office with little experience in public service, in the shadow of her wealthy father who was the top funder of her campaign — and whose aggressive spending in other House races laid out expectations for what her alliances would be.

When the Amarillo House seat in her district came open in 2023, a political operative close to Abbott called Fairly and asked if one of his sons would be interested in running.

Fairly suggested his youngest daughter might be a better candidate. She cares about people and the issues, and she’s a tough negotiator, he said.

Fairly broached the opportunity with Caroline, but refused to weigh in until she had made a choice.

“He told me, ‘This is your decision, and I don't want to have any sway or impact in it,’” Caroline said. “And by golly, he held that.”

Still, Caroline is hyper-aware of the perception surrounding her father’s political giving and her campaign. He eventually gave her half a million dollars throughout her campaign, more than 40% of her total money raised.

“I don't love it, mainly because I don't want people to think I'm entitled to something because of money or because of connections,” she said of the optics.

After winning office, Caroline knew she would have to work to earn the respect of her colleagues and distinguish her own political path.

To change sides in the speaker’s race — before she’d even been sworn into office — would invite criticism about her conservatism, her loyalty, her experience and her father.

The speaker vote

A few days before the start of the session, the elder Fairly made up his mind. He was going to reverse course on his threat to use his PAC to pressure members to vote for Cook.

First, he called Cook, who he said was gracious. Then, four days before the speaker election, Fairly released his second public announcement about the PAC. He indicated he’d no longer seek to punish candidates for their speaker vote, essentially granting them his blessing to vote for Burrows.

“The vote for Speaker belongs to the members,” Fairly wrote in his statement.

But Fairly’s move complicated things for Caroline, who was still struggling with her own decision.

If she switched alongside her father, it would fuel the accusations that he was controlling her seat.

“I want to vote for Burrows, but I can't change the optics,” she remembered thinking. “I’m with Cook. I've committed to Cook. He is my guy.”

The night before the speaker’s race, Caroline joined a call of Cook supporters where they walked through how they expected the voting rounds to go before Cook received enough votes to win.

But when Caroline woke up the next morning, she realized she couldn’t stick with them.

“When I take away the pressure, when I take the outside influence away, and what will people think about me, or will someone primary me, and I look at just the two guys: Who would I vote for?” Caroline said. “It was Dustin Burrows.”

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/f3b09936fceb06d8dbee8de226e55538/08%20-%20Burrows%20Cook%20BD.jpg)

Caroline was worried about political blowback fueled by Dunn’s allies and network. But she also recognized that because of her father and his resources, she was perhaps the member best positioned to be brave. It felt incumbent on her to take a stand for other lawmakers who she believed didn’t feel like they had the freedom to vote as they wished.

“That was part of the conviction, too,” she said. “I have some protection, and these people need to break free of this. Like, this is ridiculous.”

She released her statement a few hours before the vote.

“This vote has brought an extraordinary amount of outside pressure, with threats aimed at those who don’t support Mr. Cook,” Caroline wrote in her announcement. “While wealthy outsiders have the right to operate like this, I won’t start my tenure as your representative capitulating to outside pressures to place a vote I disagree with.”

Caroline was one of two House members who switched their vote to Burrows at the last minute.

Burrows was elected House speaker with support from 49 Democrats and 36 Republicans.

An appeal to Dunn

By the conclusion of the speaker vote, Alex Fairly’s entire view of Texas politics had shifted. The experience taught him that wealthy donors had a responsibility, a moral obligation, to tread cautiously.

“We have the ability to essentially begin to control people — either their vote or their position — because we have enough money to overwhelm a district House race,” Fairly said. “I think we have to be so careful that we have the discipline to be careful about how we go about that.”

So he went back to Dunn.

Over the next few months, Fairly said he and Dunn spoke over the phone and in person several times. Fairly tried to appeal to Dunn to dial back his network’s smear tactics and called on Dunn’s allies to support Burrows now that he was the leader of the House.

“We should coalesce around a productive way to support conservative things happening and not spend our time trying to catch [Burrows] not being conservative,” Fairly said he told Dunn.

He laid out for Dunn what he had witnessed over the past few months, including what had happened to Republican members who received the brunt of the attacks, and how it informed his changed perspective. He tried to appeal to Dunn’s faith.

Fairly declined to share specifics of how Dunn responded. Dunn did not respond to interview requests or a list of emailed questions.

Fairly said the conversations were candid and there were moments of disagreement.

“Ultimately, I think the machine is set in its ways, and it'll go forward like it goes forward,” Fairly said. “But I have to give credit where credit's due: that he sat and had a super, super honest, candid conversation.”

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/c5232249db64fdb90cfad36da637bb23/09%20-%200410%20Alex%20Fairly%20EH%20TT%2043.jpg)

Sometime after Fairly made his appeal to Dunn, Rep. Mano DeAyala, R-Houston, heard from one of Dunn’s top political operatives, Luke Macias.

DeAyala described the meeting as a gesture to mend fences after being on the receiving end of dirty primary attack ads connected to Dunn’s group.

DeAyala had previously shared his negative primary experience with Fairly — including an anti-Muslim mailer that insinuated DeAyala had voted to bring Sharia law to Texas.

“I informed [Fairly] of that as an example of how disappointed many of us have become that we are seeing those within the party bear false witness against others,” DeAyala said.

The meeting with Macias didn’t wipe the slate clean, DeAyala said, but it was humanizing. Macias didn’t respond to requests for an interview.

“I’m not saying that we’re best buds, but we’re certainly more familiar with each other and when you’re familiar with somebody it’s harder to throw daggers,” he said. “That never would have happened without Alex.”

A primary threat reemerges

Fairly doesn’t know what he’s going to do with his PAC. As of last week, he said the $20 million is still sitting in an account.

“I know more about what the PAC isn't going to do than what the PAC is going to do,” he said. “Not that the PAC won't be involved in any primaries, but its purpose isn't going to be to primary people who voted some certain way that I disagree with on some issue.”

But he does know he doesn’t want to be the state’s next Tim Dunn.

“Tim was much further along and much more sophisticated politically than I was, or am, or probably ever want to be,” Fairly said.

He doesn’t want to be the anti-Tim Dunn, either. He turned down Texans for Lawsuit Reform, a major backer of establishment Republicans, who Fairly said has also asked to join forces.

“Everyone puts people in a camp, and because I don't really just fit in one, it feels it doesn't make that much sense to people,” Fairly said. “That's just who I am, and I think I'm really comfortable with it.”

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/d430ca39f86688634d84d1762deb41dd/10%20-%200421%20Alex%20Fairly%20EH%20TT%2066.jpg)

As he recalibrates his politics, he is still holding on to some hardliner allies. Despite Paxton’s close allegiance to Dunn and his involvement as ringleader in the primary and House speaker races, Fairly has already donated to his U.S. Senate campaign challenging Sen. John Cornyn.

In a statement to the Tribune, Paxton called Fairly a “principled leader,” and applauded his “courage and conviction to stand up for what is right.”

At the same time, Fairly is warming up to Burrows.

“I think he's doing great. I'm very optimistic. I have way less doubts," Fairly said of Burrows, adding that he’s reserving final judgment for the end of the session.

Yet in late April, Fairly was miffed when he received a mass text from the chair of the Republican Party of Texas, threatening to run a primary opponent against members who did not vote to pass all the remaining bills related to the state party’s priorities.

“The Texas House is failing us, stalling on the Republican priorities YOU voted for,” the text read. “We will not tolerate cowardice or betrayal.”

Fairly called RPT Chair Abraham George and told him that broadly threatening members was unproductive.

He accused the state party of being owned by the Dunn operation, and acting as its mouth piece. The Republican Party of Texas has increasingly relied on funding from PACs funded by Dunn.

“[Dunn’s network] is the place where you can get money, whether it's their money or their friends' money,” Fairly said he told George. “But … the thing that you live on is choking the life out of you.”

George did not respond to multiple requests for comment. But shortly after Fairly said he and George ended their call, George posted on social media: “One text campaign and suddenly I'm getting calls from legislators and donors telling me to back off primaries. ... We will not!”

Exhausted by George’s continued threats against Republicans, Fairly offered one of his own.

“I'm weary of this method of trying to get what we want,” Fairly said he told George. “You’re someone who’s probably trying to get something done that I probably agree with. If this is how we're going to manage people … I may use my money to help balance this out.”

Disclosure: Texans for Lawsuit Reform, Texas A&M University and West Texas A&M University have been financial supporters of The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan news organization that is funded in part by donations from members, foundations and corporate sponsors. Financial supporters play no role in the Tribune's journalism. Find a complete list of them here.

First round of TribFest speakers announced! Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist Maureen Dowd; U.S. Rep. Tony Gonzales, R-San Antonio; Fort Worth Mayor Mattie Parker; U.S. Sen. Adam Schiff, D-California; and U.S. Rep. Jasmine Crockett, D-Dallas are taking the stage Nov. 13–15 in Austin. Get your tickets today!

This article originally appeared in The Texas Tribune at https://www.texastribune.org/2025/05/08/alex-fairly-texas-republican-donor-tim-dunn-texas-house/.

The Texas Tribune is a member-supported, nonpartisan newsroom informing and engaging Texans on state politics and policy. Learn more at texastribune.org.